The Eyes of Bayonetta 2 the Official Art Book

⌄ Scroll downward to continue ⌄

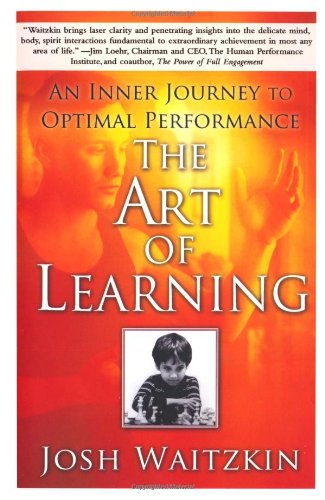

Josh Waitzkin has led a full life equally a chess master and international martial arts champion, and as of this writing he isn't notwithstanding 35. The Art of Learning: An Inner Journey to Optimal Performance chronicles his journey from chess prodigy (and the subject of the movie Searching for Bobby Fischer) to world championship Tai Chi Chuan with important lessons identified and explained forth the way.

Marketing expert Seth Godin has written and said that one should resolve to modify three things as a result of reading a business organization volume; the reader will notice many lessons in Waitzkin's volume. Waitzkin has a list of principles that appear throughout the book, but it isn't e'er clear exactly what the principles are and how they tie together. This doesn't really hurt the book'southward readability, though, and it is at best a small-scale inconvenience. There are many lessons for the educator or leader, and equally i who teaches college, was president of the chess club in middle school, and who started studying martial arts about two years ago, I found the book engaging, edifying, and instructive.

Waitzkin'southward chess career began among the hustlers of New York's Washington Foursquare, and he learned how to concentrate among the noise and distractions this brings. This experience taught him the ins and outs of aggressive chess-playing as well every bit the importance of endurance from the chary players with whom he interacted. He was discovered in Washington Square by chess teacher Bruce Pandolfini, who became his first coach and developed him from a prodigious talent into 1 of the best young players in the globe.

The book presents Waitzkin'due south life as a study in contrasts; mayhap this is intentional given Waitzkin's admitted fascination with eastern philosophy. Among the nearly useful lessons business organization the aggression of the park chess players and young prodigies who brought their queens into the action early or who ready elaborate traps and then pounced on opponents' mistakes. These are excellent ways to rapidly dispatch weaker players, but information technology does non build endurance or skill. He contrasts these approaches with the attention to item that leads to genuine mastery over the long run.

⌄ Curl down to continue reading commodity ⌄

⌄ Curlicue downward to continue reading article ⌄

According to Waitzkin, an unfortunate reality in chess and martial arts—and perhaps by extension in educational activity—is that people acquire many superficial and sometimes impressive tricks and techniques without developing a subtle, nuanced command of the central principles. Tricks and traps can impress (or vanquish) the credulous, but they are of limited usefulness against someone who actually knows what he or she is doing. Strategies that rely on quick checkmates are likely to falter against players who tin can deflect attacks and go one into a long middle-game. Bully inferior players with four-motion checkmates is superficially satisfying, just information technology does little to meliorate one'south game.

He offers one child every bit an chestnut who won many games confronting inferior opposition only who refused to cover real challenges, settling for a long string of victories over conspicuously inferior players (pp. 36-37). This reminds me of advice I got from a friend recently: e'er try to brand certain you're the dumbest person in the room and so that you're always learning. Many of us, though, draw our self-worth from being big fish in minor ponds.

Waitzkin's discussions cast chess as an intellectual boxing match, and they are particularly apt given his discussion of martial arts later in the book. Those familiar with boxing will call up Muhammad Ali'south strategy against George Foreman in the 1970s: Foreman was a heavy hitter, but he had never been in a long tour before. Ali won with his "rope-a-dope" strategy, patiently absorbing Foreman'southward blows and waiting for Foreman to exhaust himself. His lesson from chess is apt (p. 34-36) as he discusses promising young players who focused more intensely on winning fast rather than developing their games.

Waitzkin builds on these stories and contributes to our understanding of learning in chapter two by discussing the "entity" and "incremental" approaches to learning. Entity theorists believe things are innate; thus, 1 can play chess or do karate or be an economist because he or she was born to do so. Therefore, failure is securely personal. By contrast, "incremental theorists" view losses as opportunities: "step by step, incrementally, the novice can become the main" (p. xxx). They rise to the occasion when presented with difficult fabric because their arroyo is oriented toward mastering something over time. Entity theorists collapse under force per unit area. Waitzkin contrasts his approach, in which he spent a lot of time dealing with end-game strategies

where both players had very few pieces. By dissimilarity, he said that many young students begin past learning a wide assortment of opening variations. This damaged their games over the long run: "(one thousand)any very talented kids expected to win without much resistance. When the game was a struggle, they were emotionally unprepared." For some of u.s., pressure level becomes a source of paralysis and mistakes are the beginning of a downwards screw (pp. 60, 62). As Waitzkin argues, withal, a different approach is necessary if we are to accomplish our full potential.

A fatal flaw of the stupor-and-awe, blitzkrieg arroyo to chess, martial arts, and ultimately annihilation that has to be learned is that everything can be learned past rote. Waitzkin derides martial arts practitioners who go "form collectors with fancy kicks and twirls that have absolutely no martial value" (p. 117). One might say the aforementioned affair well-nigh problem sets. This is not to gainsay fundamentals—Waitzkin's focus in Tai Chi was "to refine certain fundamental principles" (p. 117)—just there is a profound departure between technical proficiency and true agreement. Knowing the moves is one matter, but knowing how to make up one's mind what to do next is quite another. Waitzkin's intense focus on refined fundamentals and processes meant that he remained stiff in subsequently round while his opponents withered. His approach to martial arts is summarized in this passage (p. 123):

⌄ Curlicue down to go along reading article ⌄

⌄ Roll down to keep reading article ⌄

"I had condensed my body mechanics into a potent land, while almost of my opponents had large, elegant, and relatively impractical repertoires. The fact is that when there is intense competition, those who succeed have slightly more honed skills than the rest. It is rarely a mysterious technique that drives us to the height, just rather a profound mastery of what may well exist a basic skill set. Depth beats breadth any day of the week, considering information technology opens a channel for the intangible, unconscious, creative components of our hidden potential."

This is about much more than than smelling blood in the water. In chapter 14, he discusses "the illusion of the mystical," whereby something is then clearly internalized that well-nigh imperceptibly small movements are incredibly powerful as embodied in this quote from Wu Yu-hsiang, writing in the nineteenth century: "If the opponent does non move, then I practise not move. At the opponent's slightest move, I move first." A learning-centered view of intelligence ways associating effort with success through a process of instruction and encouragement (p. 32). In other words, genetics and raw talent tin just get yous so far earlier hard work has to pick up the slack (p. 37).

Some other useful lesson concerns the use of adversity (cf. pp. 132-33). Waitzkin suggests using a trouble in one surface area to adapt and strengthen other areas. I take a personal case to back this up. I will e'er regret quitting basketball in high school. I recollect my sophomore year—my concluding twelvemonth playing—I broke my pollex and, instead of focusing on cardiovascular conditioning and other aspects of my game (such equally working with my left hand), I waited to recover before I got dorsum to work.

Waitzkin offers some other useful chapter entitled "slowing downwards fourth dimension" in which he discusses ways to acuminate and harness intuition. He discusses the process of "chunking," which is compartmentalizing problems into progressively larger problems until 1 does a complex set of calculations tacitly, without having to think about information technology. His technical example from chess is specially instructive in the footnote on page 143. A chess grandmaster has internalized much about pieces and scenarios; the grandmaster can procedure a much greater amount of information with less effort than an practiced. Mastery is the procedure of turning the articulated into the intuitive.

In that location is much that will exist familiar to people who read books similar this, such as the need to stride oneself, to gear up clearly defined goals, the demand to relax, techniques for "getting in the zone," and and so forth. The anecdotes illustrate his points beautifully. Over the course of the volume, he lays out his methodology for "getting in the zone," another concept that people in performance-based occupations will find useful. He calls it "the soft zone" (chapter three), and it consists of beingness flexible, malleable, and able to adapt to circumstances. Martial artists and devotees of David Allen's Getting Things Done might recognize this as having a "mind like water." He contrasts this to "the difficult zone," which "demands a cooperative world for you to function. Like a dry twig, you are brittle, set up to snap nether pressure" (p. 54). "The Soft Zone is resilient, like a flexible bract of grass that can movement with and survive hurricane-force winds" (p. 54).

⌄ Ringlet down to continue reading commodity ⌄

⌄ Scroll down to continue reading article ⌄

Some other illustration refers to "making sandals" if one is confronted with a journeyacross a field of thorns (p. 55). Neither bases "success on a submissive world or overpowering forcefulness, but on intelligent preparation and cultivated resilience" (p. 55). Much hither will exist familiar to creative people: yous're trying to think, but that one song by that one band keeps blasting away in your head. Waitzkin's "only choice was to become at peace with the noise" (p. 56). In the linguistic communication of economics, the constraints are given; we don't get to choose them.

This is explored in greater detail in chapter sixteen. He discusses the top performers, Michael Jordan, Tiger Woods, and others who do non captivate over the last failure and who know how to relax when they need to (p. 179). The feel of NFL quarterback Jim Harbaugh is also useful as "the more he could let things go" while the defense was on the field, "the sharper he was in the adjacent drive" (p. 179). Waitzkin discusses further things he learned while experimenting in homo performance, especially with respect to "cardiovascular interval training," which "tin have a profound effect on your ability to quickly release tension and recover from mental exhaustion" (p. 181). It is that last concept—to "recover from mental burnout"—that is likely what near academics need assistance with.

There is much here nearly pushing boundaries; however, one must earn the right to do so: every bit Waitzkin writes, "Jackson Pollock could draw like a photographic camera, but instead he chose to splatter paint in a wild manner that pulsed with emotion" (p. 85). This is another good lesson for academics, managers, and educators. Waitzken emphasizes close attending to detail when receiving teaching, particularly from his Tai Chi instructor William C.C. Chen. Tai Chi is non virtually offering resistance or force, but about the ability "to blend with (an opponent'south) free energy, yield to it, and overcome with softness" (p. 103).

The book is littered with stories of people who didn't achieve their potential because they didn't seize opportunities to improve or because they refused to adapt to atmospheric condition. This lesson is emphasized in affiliate 17, where he discusses "making sandals" when confronted with a thorny path, such every bit an underhanded competitor. The book offers several principles by which we can become better educators, scholars, and managers.

Celebrating outcomes should be secondary to celebrating the processes that produced those outcomes (pp. 45-47). At that place is also a study in contrasts beginning on page 185, and it is something I have struggled to learn. Waitzkin points to himself at tournaments being able to relax betwixt matches while some of his opponents were pressured to analyze their games in between. This leads to extreme mental fatigue: "this tendency of competitors to exhaust themselves betwixt rounds of tournaments is surprisingly widespread and very self-subversive" (p. 186).

⌄ Scroll down to proceed reading article ⌄

⌄ Ringlet down to continue reading article ⌄

The Art of Learning has much to teach us regardless of our field. I found information technology particularly relevant given my chosen profession and my determination to start studying martial arts when I started teaching. The insights are numerous and applicable, and the fact that Waitzkin has used the principles he now teaches to become a world-class competitor in ii very demanding competitive enterprises makes information technology that much easier to read.

I recommend this book to anyone in a position of leadership or in a position that requires extensive learning and accommodation. That is to say, I recommend this book to everyone.

More Well-nigh Learning

- 13 Ways to Develop Self-Directed Learning and Learn Faster

- How to Learn Fast and Think More: 5 Effective Techniques

- How to Create an Effective Learning Process And Learn Smart

Featured photograph credit: Jazmin Quaynor via unsplash.com

Source: https://www.lifehack.org/articles/lifehack/a-review-of-the-art-of-learning.html

0 Response to "The Eyes of Bayonetta 2 the Official Art Book"

Post a Comment